The Energy Council News

See our latest info and updates. Don’t forget to checkout our Member Spotlight.

Facts about the energy industry

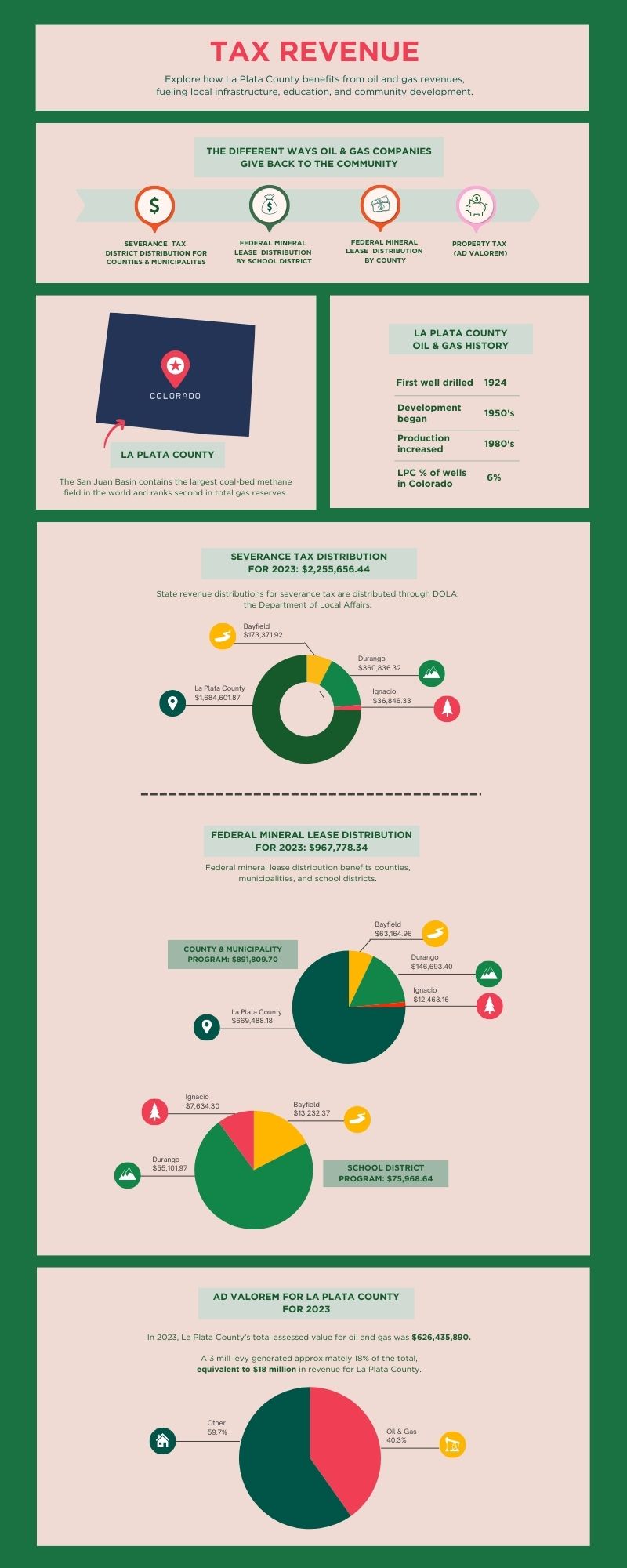

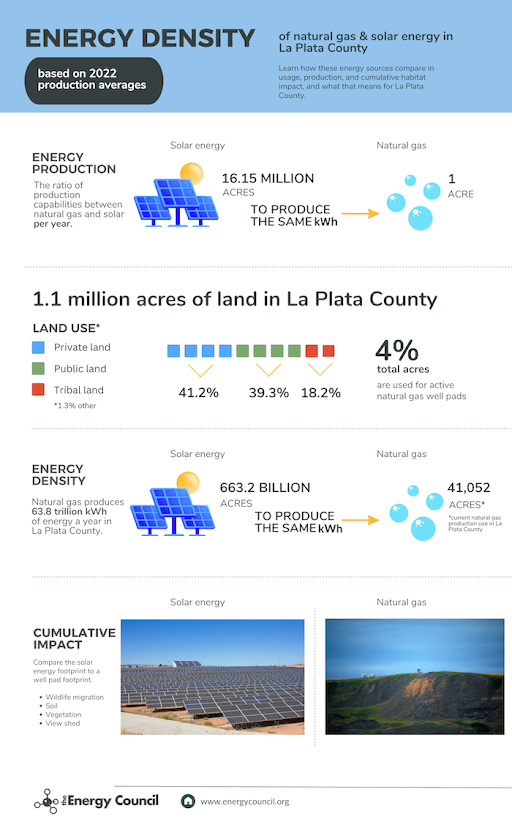

The Energy Council is a nonprofit trade organization serving Archuleta, Dolores, La Plata, and Montezuma Counties. We promote safe and responsible oil, natural gas, and carbon dioxide (CO2) development, because these energy sources are a cornerstone of the United States and Southwestern Colorado Economies. In 2019, U.S. energy production exceeded U.S. energy consumption on an annual basis for the first time since 1957. The three major fossil fuels—natural gas (35%), petroleum (31%), and coal (14%) —accounted for about 80% of total U.S. primary energy production. Renewable energy accounted for 12% and nuclear power was 8%.

Energy Infographics

FAQs about gas

ABOUT NATURAL GAS (CH4)

Natural gas is one of the safest, cleanest, and most versatile energy sources. Additionally, it is extremely powerful and abundant, making it the heat source for more than half of all homes in the United States, and a significant percentage of Americans use natural gas to cook and heat water. Many people don’t know that natural gas is also a raw material used to produce petrochemicals, plastics, paints, and for powering industrial furnaces in many manufacturing contexts. In the last decade natural gas has become the fuel of choice for the next generation of electric power plants. Methane naturally leaks into the atmosphere through natural seeps and crevices where the surface of a coal formation is exposed to the surface of the earth. Outcrops occur naturally all around the San Juan Basin.

Fast Facts

- More than 62 million homes use natural gas to fuel stoves, furnaces, water heaters, clothes dryers, and other household appliances.

- Natural gas is an essential raw material for many common products, such as plastics, fertilizers, paints, antifreeze, dyes, photographic film, and medicines.

- Natural gas is composed of four hydrogen atoms and one carbon atom (CH4) and is also commonly called methane.

- Colorless and odorless in its natural state, natural gas is the cleanest burning fossil fuel.

- Natural gas provides approximately 35% of our electric power. Gas turbine and steam generating plants use natural gas. A combined-cycle system is the most efficient.

- Propane is a byproduct of natural gas and is the primary heating fuel for homes in much of rural Colorado

- La Plata County produces the most natural gas in the State of Colorado from the fewest wells.

- The San Juan Basin (which includes La Plata and Archuleta Counties) is the top producer of coalbed methane natural gas in the United States.

- Three years ago, Colorado ranked 5th in the nation for natural gas onshore production. Today, Ohio and Pennsylvania both produce more natural gas than Colorado, dropping our state to 7th.

ABOUT CARBON DIOXIDE (CO2)

The Paradox Basin is located under Dolores and Montezuma Counties, and is a much different basin than the San Juan Basin due to its production of a completely different gas product. Parts of the Paradox Basin traditionally produced conventional oil and gas, but recently, Ute Dome and Barker Dome in Montezuma and Dolores Counties have also been producing substantial amounts of CO2.

Fast Facts

- The McElmo Dome Unit is one of the largest deposits in the nation of nearly pure CO2

- Montezuma and Dolores County operators are number one for CO2 production in the entire State of Colorado and the largest transporters of CO2 in North America.

- The CO2 extracted from the McElmo Dome Unit is compressed and transported across New Mexico, Texas, and Utah

- CO2 extraction has provided secondary use for oil wells that can no longer efficiently recover the oil in place.

- CO2 is known as “the miracle molecule” due to its wide application of uses

- It is used for refrigeration, fire extinguishers, safe food transportation, and the carbonation of drinks.

- CO2 is used in the Permian basin to Frac as a safe and efficient alternative for water or sand

LOCAL PRODUCTION OVERVIEW:

The San Juan Basin is approximately 270 miles wide, north to south. Its five counties together contain over four million acres of land and contain three climatic zones — mountains, deserts, and mesas. The Basin covers over 6,700 square miles and is the second largest natural gas reserve in the United States.

Archuleta and La Plata Counties are two of the counties within the San Juan Basin with primary production of natural gas in three different geological formations, the Fruitland Coal, Mesa Verde, and Dakota. Depths in the middle of the basin are between 2,500’ (Fruitland Coal) and 7,800’ (Dakota). Because the San Juan Basin is so rich in natural gas deposits, production from the Fruitland Coal and Mesa Verde formations in both Archuleta and La Plata Counties will be active for many decades to come. Active well counts vary by county and from month to month. The chart below indicates the net change in active wells from December 2017 to December 2020 in the four counties represented by the Energy Council.

|

Location |

Active Well Count |

% of Colorado’s Total Active Wells |

||

|

December 2017 |

December 2020 |

December 2017 |

December 2022 |

|

|

State of Colorado |

55,059 |

50,840 |

100% |

100% |

|

Archuleta County |

148 |

159 |

0.27% |

0.31% |

|

Dolores County |

41 |

39 |

0.07% |

0.05% |

|

La Plata County |

3,340 |

3,262 |

6.1% |

6.42% |

|

Montezuma County |

165 |

152 |

0.29% |

0.10% |

In 2002, United States Geological Survey estimated a mean of 50.6 trillion cubic feet of unrecovered natural gas in the San Juan Basin. Twenty years later, it is still expected that natural gas development in La Plata and Archuleta Counties will continue for several decades.

As new technologies have evolved, the San Juan Basin has shown that is the basin that just keeps giving. Development in other formations, such as the Mancos Shale, has begun in northern New Mexico, just south of La Plata and Archuleta Counties.

Types of Local GAS WELLS:

There are two types of natural gas wells in La Plata and Archuleta Counties, conventional and coalbed.

|

Conventional Gas Wells |

Coalbed Gas Wells |

|

|

Conventional and coalbed methane gas wells are significantly deeper than domestic water wells. Natural gas wells are separated from the surrounding surface formations by “casings” discussed below. Geologic studies show that beds of nearly impermeable shale separate deep and shallow aquifers and retard vertical water movement.

Shale is sedimentary rock that forms when silt and clay-size mineral particles are compacted. Shale resources are found in shale formations that contain significant accumulations of natural gas and/or oil. The natural gas industry generally distinguishes between two categories of low-permeability formations that produce natural gas: shale natural gas and tight natural gas. In both La Plata and Archuleta Counties, the Mesa Verde and Niobrara formations are tight natural gas formations

What do pump jacks do?

Pump jacks at well sites are used to pump water and sometimes oil — not gas. On a conventional gas well a pump jack is not necessary at the beginning but may be added later to remove the increasing amounts of water. On a coalbed well, a pump jack is typically needed during the first few years and can be removed as the amount of water declines.

What is the lifetime of a well?

All wells vary in the duration of natural gas production. Depending on a number of factors, wells can produce from a few years to 40 or 70 years. As advances in natural gas production continue, well duration may change based on how technology affects recovery.

During the productive life of a well operators are responsible for various types of maintenance associated with the well as stipulated in the lease or other legal documents, and as may be required by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC). Regulations and obligations include compliance with any applicable health, safety, welfare, environment, and wildlife regulations or agreements.

How is the location of a well decided? Can a well be placed anywhere?

In today’s natural gas, oil, or CO2 industries, the first step in the life cycle of a well begins with the understanding of and compliance with government regulations. Each formation currently conducive to natural gas extraction is spaced by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC). This means that the COGCC has determined how many wells per section will adequately drain the resource (a section generally consists of 640 acres). The Fruitland formation in both La Plata and Archuleta Counties is generally spaced at one well per 160 acres, with certain areas of the counties spaced at 80 acres. The Pictured Cliffs and Mesa Verde formations in La Plata County are spaced at one well per 320 acres and the Dakota formation is spaced at 640 acres. In the Red Mesa field, oil wells in the Dakota formation are spaced at approximately one well per 40 acres. For more information about specific spacing in formations in a certain location, you can review Orders for counties on the COGCC website.

The diagram above shows how a 640-acre section is divided for 160-acre spacing. To assure correlative rights, an operator must produce gas from the “drilling window” thousands of feet below the surface. At the surface, the drilling window is a starting point from which operators seek to locate a well site.

Sometimes a gas well may be located outside the window when special circumstances arise such as above ground geography or a special landowner request — typically agriculture-related.

Wildcat wells are often referred to as exploratory or exploration wells, and are the first wells to be drilled in a geographic region. For a wildcat well, spacing and setback to assure correlative rights are prescribed by COGCC Order. Drilling deviated wells are becoming more common, it is the angle at which a wellbore diverges from vertical. Wells can deviate from vertical deliberately and are often deviated or turned to a horizontal direction to increase exposure to producing zones.

How are mineral rights involved in oil and gas production?

The potential producer must acquire the right to develop the natural gas reserve. Typically, a natural gas operating company (operator) acquires a lease for mineral rights by entering into a contractual agreement with the mineral owner. The mineral owner receives royalties from any production that may result. In addition to a lease agreement with the mineral owner, an operator must obtain a local permit and a state permit, or a federal permit, depending on the ownership of the minerals.

The operator or producer can sever the formations and assign certain formations to another operator to develop the property right.

What goes into building a new well?

- Spacing: In today’s natural gas, oil, or CO2 industries, the first step in the life cycle of a well begins with the understanding of and compliance with government regulations. Each formation currently conducive to natural gas extraction is spaced by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC). This means that the COGCC has determined how many wells per section will adequately drain the resource (a section generally consists of 640 acres).

- Siting and Consultation: The next step includes geologic and seismic studies to locate the best possible underground source of natural gas, either in sandstone or coal formations. After the studies are completed, companies typically select an optimal site. Then well location and right-of-way easements for road access are negotiated with the surface owners. During this phase companies work closely with surface owners to locate the well site within the regulated spacing window. Operators strive to minimize the surface use and are using existing roads and infrastructure where possible and feasible. The COGCC requires multiple consultations with local governments, and other state and federal agencies, and requires analysis of alternative locations and cumulative impacts of the operations. Local governments have their own criteria for citing and their Local Government Designee is also noticed on a variety of topics from rig movements to abandoned flow lines.

- Permitting is conducted in accordance with COGCC rules and local government land use rules. For efficiency, operators permit concurrently with the state and local or federal governments. COGCC permitting rules are prescriptive and comprehensive and require multiple plans, alternative locations, address cumulative impacts, surrounding impacts, mitigation to wildlife, and water protection in order to protect the health, safety, welfare, environment, and wildlife. Permitting agents arrange notice and consultation according to rules or regulations, and for transparency, all permits can be found on the COGCC website.

- Drilling a gas well is a highly orchestrated event usually done by drilling contractors. Drilling contractors are rigorously trained to work efficiently and safely. Drilling rigs and crews are expensive and brought on the site for immediate action. Because of the safety, technical concerns, and expense, drilling rigs operate 24 hours a day until the drilling is completed. For example, if drilling is stopped, the drilled hole can cave in and potentially cause multiple safety and environmental problems. Once drilling is completed, the rig and crew move to another location.

- Completion not only refers to the target formation, “the completion zone,” but is also a term used to describe well construction activity after the drilling and casing is finished. To complete a well, the permeability of the completion zone must be enhanced so that gas can flow out of the sandstone or coalbed in which it is trapped. To enhance permeability hydraulic fracture stimulation (commonly referred to as “fracking”)may be conducted. Not all wells in Archuleta, Dolores, Montezuma, and La Plata Counties require fracking.

- Interim Reclamation: After a well is drilled, all areas which were disturbed by the drilling operations, and which are not needed for production operations, are to be reclaimed as close to their original condition as possible.The interim reclamation is required by several COGCC rules. Operators revegetate the landscape, re-contour, till the soil, reseed, and conduct weed and soil erosion prevention. Sometimes interim restoration and revegetation is negotiated in the surface agreement with the landowner, and is consistently inspected by the appropriate agency.

What happens to the product after it is pumped out of the ground?

Production: After completion of the well, pipeline construction connects the well to the natural gas, oil, or CO2 produced from a well and is separated from the gas at the well site. Water is transported off the well site in one of two ways, by pipeline or by truck.

Compression: Natural gas, oil, and CO2 are transported in pipelines. The amount of gas, oil, or CO2 that can be transported in a pipeline depends upon how much the products are compressed, and the capacity of the pipeline. The more the gas or other product is compressed, the greater the volume of gas or other products that can be transported through the pipeline. Uncompressed gas or other product is displaced by compressed products or gas, essentially stopping the flow of uncompressed gas or other products to the processing plant.

Compression can either take place right at the well site as it enters the pipeline system, or it can be transported by pipeline to a compression facility, where it is compressed and then transported to a processing plant. On-site compression is done with small electric or gas-powered compressors. A compression facility contains large electric or gas-powered compressors and is surrounded by a sound absorbing structure. The type of compression used by companies depends upon economic factors and well location concerns — the more remote a well is, the more difficult it will be to tie the well into a compression facility. Some companies try to cluster well sites so that a centrally located compression facilities can serve the needs of many wells, thus reducing the noise associated with compression

Processing: Safety and environmental protection are top priorities at local processing plants. Safety training, regular safety meetings, emergency drills, coordination with local fire departments and emergency personnel are all part of normal operations. Plants must also meet strict federal safety and environmental standards and comply with state and local regulations.

At these plants, raw gas, oil, or CO2 is processed to remove undesirable components such as water and separated into distinct products such as methane, ethane, butane, propane, and others. One plant in La Plata County supplies the majority of propane used in a 150-mile radius.

The processed natural gas, oil, or CO2 travels through other pipelines to commercial markets around the United States.

How are wells drilled? What does the inside of a well look like?

Anywhere from one to three acres are needed for the drilling pad; however, pads can be much larger if deviated/directional drilling is employed for the shale formations. The well pad is prepared for a variety of heavy equipment needed during the drilling operation. After drilling is completed and interim reclamation is complete, the size of the well pad is reduced.

The drilling process requires the power of multiple diesel engines. Actual drilling time can be anywhere from 3 to 10 days — more for directionally drilled or deeper zone wells. State noise regulations allow for short-term construction noise within prescribed safety limits. Sound diminishes with distance, but precautions are taken for workers in close proximity to sound sources. Nearby residents are notified in advance of drilling activity.

Typically, well drilling to casing goes like this — a 12-1/4″ diameter hole is drilled to a minimum of 200 feet and to maximum depth 50 feet below the deepest registered domestic water well in the area. Depth to groundwater is determined by using depth recordings from nearby well permit applications on file with the Colorado Division of Water Resources. Surface casing is put into this hole. Surface casing is 1/2″ thick steel pipe with an outside diameter of 8-5/8″. Cement is poured between the hole and the steel casing and is approximately 2″ thick all the way up to the surface. The cement is allowed to dry, then the 7-7/8″ production hole is drilled 200 feet below the target formation, also known as the completion zone. Production casing is then put into the hole. Production casing is 3/8″ steel pipe with an outside diameter of 5-1/2″. Again, cement is poured between the hole the steel casing measuring about 1″ thick all the way up to the surface.

Cement seals off formations to prevent fluids from migrating. For example, cement protects fresh water in one formation from methane gas in another. Cement also protects the steel casing from the corrosive effects of other formation fluids. Casings are checked for integrity before the well construction process continues. In some deeper natural gas wells, intermediate casing is needed because some formations are encountered that contain abnormal pressures and/or conditions.

In the completion zone, the production casing is perforated so that natural gas or other products can flow into the production tubing. Production tubing is set in place after the completion process and is 1/4″ steel tubing with an outside diameter of 2-7/8″ running from the bottom of the hole to the surface.

At the bottom of the hole, 40 feet of cement is poured with a plastic plug on top to complete the sealed well bore.

In comparison domestic water wells are required to be cased with only 0.188″ steel pipe, or 0.2″ plastic pipe, or 3″ cement, with a minimum 4-1/2″ outside diameter.

Gas wells are separated from the surrounding surface formations by 4-1/8″ of steel pipe and cement that make up a well’s casing. Casing is designed, among other things, to isolate gas wells from any nearby domestic water wells. This diagram is not to scale and has been dramatically shortened.

What is fracking? Does it occur in Southwestern Colorado?

Hydraulic fracturing is a technology used to stimulate the flow of oil and gas from new and existing oil and gas wells by pumping water, sand, and small amounts of chemicals under pressure into geological formations that would otherwise not be able to produce the oil and or gas they contain. Hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” as it is commonly known is a proven safe procedure that has been used millions of times in the last 60 years across the country, including Archuleta, Montezuma, Dolores, and La Plata Counties. It should be noted, not all wells need to be fracked.

For specific information regarding chemicals used and water used on individual natural gas or oil wells by county use the following link: FracFocus. (Note this will take you to an external page.)

Many rigorous studies have been conducted by respected authorities, and they have all concluded that hydraulic fracturing is safe.

What happens to wells after they stop being productive?

There are a few terms that are commonly used to describe things that can happen at the end of a well’s life.

Workover: During the life of a well, it may need additional work to improve performance; this is called a workover. Other workover activities will result in temporary rig activity on the well pad.

Recompletion: Recompletion is a way of reusing an existing well to capture more natural gas or other products from either the same formation or different formations. Recompletion means changing or adding completion zones (target formations) through one of the following ways: 1) recompletion to the same zone but to the side of the original hole, 2) recompletion to a different zone, or 3) recompletion to multiple zones from one well. Recompletions require rig activity that lasts for several days.

Temporary Shut-in: Sometimes the price of natural gas or other products is so low that the cost to produce and process it is higher than the production revenue which creates a situation where economics dictate that the well be temporarily shut-in. The well may later be returned to production. This temporary shut-in is highly regulated by the COGCC for safety and reporting purposes.

Plugging and Abandonment: After all the recoverable natural gas, oil, or CO2 has been drained at a well site, the well is plugged and abandoned and notifications are provided to the appropriate governments. The COGCC has rules that specify how the well is to be plugged, soil testing to be performed, and reclamation and other environmental and safety protections.

Some wells were plugged and abandoned prior to the COGCC’s rules, and in some cases old wells have been “orphaned.” The state has a special fund supported by natural gas severance taxes for the plugging and abandonment of orphaned wells in the state. An orphaned well is a well for which an owner or operator cannot be found or is unwilling or unable to plug and abandon the well. In these instances, required bond and fund money paid by industry is used by the COGCC to plug the orphaned well.

REGULATION’S & ACCOUNTABILITY

How does the COGCC partner with local producers?

The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) regulates the oil, CO2 and gas drilling and production industry in Colorado. Depending on the location of the minerals, other regulatory bodies may also regulate surface and downhole development such as the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and local governments. Primarily in Archuleta, La Plata, Montezuma, and Dolores Counties it is the COGCC. Siting and certain other provisions can also be found in local land use codes.

The mission of the COGCC is to regulate the development and production of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner that protects public health, safety, welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources. Responsible development balances efficient exploration and production of oil and gas with the prevention of waste and protection of mineral owner’s rights.

The COGCC issues permits for the drilling and operation of oil and gas wells and enforces rules and regulations for the spacing of wells, well bore construction, and well site reclamation. Rules are also enforced for the abandonment of wells and for the treatment and disposal of oil and gas exploration and production waste. COGCC rules implement the statutory charge to prevent significant environmental impacts to air, water, soil, or biological resources caused by oil and gas operations. To read the complete COGCC Rules or to review the index or Rules or any specific series of Rules please visit COGCC Rules

The COGCC is staffed with field inspectors, engineers, and environmental protection specialists who are responsible for reviewing permit applications and other technical information, and for inspecting oil and gas wells for compliance with COGCC regulations. These staff members also respond to complaints about oil and gas well sites by surface owners and local governments. In addition to the main Denver office, the COGCC inspectors and field engineers are located throughout the state including Durango. To see the leaders of this regulatory body, please visit COGCC Professional Commissioners or COGCC Staff Maps.

How do oil and gas companies demonstrate accountability for community safety and environmental impact?

New regulations by the COGCC became effective January 15, 2021, which included changes to the state’s regulation of subjects from drilling, completion, and production activities to subjects such as such as weed control, dust, fencing, sound, lighting associated with the well site, pipelines, and roads. Wells are also required to be pressure tested so that potential leaks can be avoided. COGCC requires environmental protections during and after production and conduct thousands of inspections on wells sites and associated facilities every year.

The COGCC requires an operator to consult with other agencies and with the surface owner for well locations, access roads, wildlife protection, and reclamation. Operators typically negotiate a surface agreement regarding the “reasonable use” of the surface during drilling, production, and ultimately the reclamation of the well site. In practice, companies generally pay surface owners for limited land use despite the fact that the law permits reasonable access and use without compensation.

What does energy production look like on Native American Lands?

The Southern Ute Indian Tribe Department of Energy oversees the development of tribal energy resources on the Southern Ute Indian Reservation. There is more information about the responsible development of these assets at: Southern Ute Department of Energy

How does the oil and gas industry practice conscientious use of water?

Along with natural gas, water also is produced from a well, and is separated from the gas at the well site. Water is transported off the well site in one of two ways, by pipeline or by truck. A pipeline system transports the produced water to an injection well. Injection wells are drilled into deep formations, often below 10,000 feet. The EPA has regulations for most injection wells, which are also overseen by the COGCC. These regulations are specifically designed to prevent contamination of underground sources of drinking water.

Water is used in the drilling and completion phases of natural gas exploration and production. During drilling, water is used to cool the drill bit and provide a mechanism to bring drill cuttings to the surface. Water is also used for hydraulic fracturing. Operators can procure water supplies from various sources but must adhere to state water law when obtaining and using water.

COGCC Rules contain provisions and reporting for volume of all surface water and Groundwater to be used, including the percentage of the total volume that is anticipated to be reused or recycled water.

In April of 2000 field wide spacing was approved by the COGCC. Special considerations in the Order 112-156 and 112-157 provide for water well testing. The water well testing criteria is specific as to the location of coalbed methane wells. The Order requires testing of water wells near the new or proposed coalbed methane wells before they are drilled and after completion operations, which include hydraulic fracturing. Additional tests are also performed at three-year intervals. Copies of all test results described above shall be provided to the COGCC, La Plata County, or Archuleta County in addition to the landowner where the water quality testing well is located within three (3) months of collecting the samples used for the test. The Rules were significantly changed in November of 2020. See COGCC Rules 614d, 615b and 615d for more information on the State water well testing programs.

How do operators obtain water rights?

Pursuant to Colorado water law and ruling by the Colorado Supreme Court concerning water production from coalbed methane natural gas wells, many operators filed water right applications with the Division 7 Water Court in Durango, CO to confirm the right to produce water from existing and proposed wells in the San Juan Basin. Operators have applied for and have received water well permits for coalbed methane natural gas wells, and have also obtained approval of Substitute Water Supply Plans (described below). Plans for Augmentation and Substitute Water Supply Plans. A plan for augmentation is a water court-approved plan that allows an out-of-priority diversion of water (such as well pumping), while ensuring that a replacement water supply is provided to the stream system in the times, location, and amounts necessary to prevent injury to vested senior water rights.

Replacement water supplies may include leased or purchased reservoir storage, direct flow water rights, non-tributary ground water, or other sources such as transbasin water supplies and recharge projects. Replacement water must be of sufficient quality and quantity to meet the requirements for which the senior water right normally been used. Plans for augmentation are generally permanent in duration. Substitute Water Supply Plans (SWSPs) are temporary plans, similar to augmentation plans, that are approved administratively by the state engineer. SWSPs are approved for periods of not more than one year, and must be renewed annually. Often, a water user will obtain approval of an SWSP while an application for approval of a permanent augmentation plan is pending in Water Court. In the San Juan Basin, operators have filed applications in the Division 7 Water Court for approval of plans for augmentation to replace out-of-priority depletions associated with coalbed methane wells that withdraw tributary ground water. These operators have also obtained approval of SWSPs to provide for replacement of depletions while the water court applications are pending.

How does the oil and gas industry monitor its impact on atmospheric methane levels?

In October 2004, Public Law 108–336 in the 108th Congress was passed which provided for the implementation of air quality programs developed in accordance with an Intergovernmental Agreement between the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and the State of Colorado concerning Air Quality Control on the Southern Ute Indian Reservation, and for other purposes. The purpose of the Public Law is to provide for the implementation and enforcement of air quality control programs under the Clean Air Act. Residents can access real time information on air quality conditions within the Reservation, with a color rating system to help people understand when air quality can be harmful to their health. For more information, see Tribe Real Time Air Quality Monitoring

Further, the lands North of the Ute Line, north of U.S. Highway 160, are regulated by the State of Colorado Air Quality Control Division under the Department of Health and Environment and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Residents can access real time information using this website with a color rating system. Visit State Real Time Air Quality Monitoring to see more.

Why did NASA’s methane study provide limited insight on the impact of the oil and gas industry on global air quality?

In August 2016, a study was released on methane emissions in the Four Corners region by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The study was narrow in scope and Energy Council members expected a more comprehensive analysis. NASA initiated its study after satellite images captured from 2003-2009 visually depicted the region with methane levels about 50 parts per billion (ppb), or 3 percent above common background levels of approximately 1,800 ppb. NASA’s study estimated methane levels from well sites in New Mexico and Colorado. Certain operational events, such as scheduled maintenance downtime, are temporary and can skew results. For example, one gas plant was measured five times, with one outlier measurement that occurred during a scheduled maintenance event. In other cases, emissions were found on a tank but without an operational understanding of the equipment purposes. Some tanks are designed to vent natural gas for safety purposes, for example. For decades, it has been known by the states and tribes in the Four Corners that natural methane seeps occur throughout the area from the Fruitland Formation outcrop. The topography of the area traps air and causes methane to build up over time, whether from human or natural sources. Oil and natural gas production began in the Four Corners’ San Juan Basin and has been produced consistently since the 1940s.

In the northwestern New Mexico portion, only half of the wells drilled are producing as of 2022 (11,000 producing wells) as of 2022. In the southwestern Colorado portion, there are approximately 2,800 active wells, about two-thirds of which are coalbed methane (CBM) and one-third conventional natural gas wells. The table below indicates the change in production from 2015 to today (data obtained from Drilling Edge).

In September 2017 satellite images captured from 2003-2009 are representative of emissions gathered in the April 2015 airplane measurements and also those reported to the EPA by industry. Interestingly gas production does not correlate with the leakage found, since gas production from both coalbed methane and conventional natural gas wells have declined. Other conclusions:

- The majority of the Four Corners emissions are coming from New Mexico. It should be recognized that most pumping engines used in New Mexico are run on natural gas, while most pumping engines used in Colorado are electric.

- The airplane real time measurements did not go south of Bloomfield, NM, where oil is produced.

- Four Corners is not the only “hot spot” in the nation.

- Methane is a naturally occurring compound in the air we breathe and does not represent a direct or significant health risk in the Four Corners region.There is a built-in economic incentive for producers to minimize emissions and capture as much methane as possible, since it is the very product they sell.

How is methane leaking accurately monitored in Southwestern Colorado?

Methane enters the atmosphere through natural seeps and crevices when the surface of the Fruitland Coal formation is exposed to the surface of the earth. Outcrops occur naturally all around the San Juan Basin. Think of it as a bowl with the edges on the surface of the earth and the bowl being where production of natural gas or oil occurs. These are natural, and not fugitive emissions, which differ from production equipment or man-made conditions. The COGCC contracted with the Colorado Geological Survey (CGS) to create a geologic map along 23 miles of Fruitland Formation outcrop to depict detailed exposures of coal east of the La Plata/Archuleta County lines. The COGCC established the 3M (Mapping, Monitoring, and Modeling) Project in April of 2000 to develop a more comprehensive understanding of outcrop seepage. In 2007, the COGCC expanded the study to include a fourth M – Mitigation. See the 2020 4M reportAn example of the emissions from monitoring seven seepage areas North of the Ute Line is as follows as directed by the COGCC.

The natural seeps along the Southern Ute Indian Reservation are approximately 18 miles long and extend from the Colorado/New Mexico state line north to the Ute line. For now, this is proprietary data but it can be assumed that there are large volumes of natural gas emitted from this contiguous formation.

Events, Community Contributions, and Scholarships

Since the Energy Council’s first fundraising golf tournament in 1996, we have raised and distributed over $200,000.00 through scholarships and numerous community grants in La Plata County. This tournament had been supported by the members of the Energy Council. Each year the Energy Council continues to host an event that enables us to increase our positive impact where we operate. This year the goal is to raise $25,000.00 for this community giving program.

Scholarship 2024 - 2025

Must be a member.